The COVID-19 crisis has changed how people access medical care and has ushered in the new era of telemedicine. Almost overnight, patients stopped going to hospitals and are, instead, receiving medical care through various online platforms.

New Delhi-based Sitaram Bharti Hospital immediately started telehealth consultation service and emergency ambulance service as soon as the Government of India announced nationwide lockdown due to COVID-19 outbreak. Likewise, Aravind Eye Care Systems in Madhurai could set up a make-shift telehealth consultation option on their hospital website in just two days. On 22 March, a team of 18 doctors at Aravind Eye Care Systems was ready to take the patients’ calls from six different locations across South India. The high number of patients who wanted telehealth consultation service resulted in the hospital setting up parallel windows in each of their eight branches using Google Hangout. It was a right move in the anticipation of a bigger lockdown that was announced a couple of days later. Similarly, Nagarajan Ramakrishnan, a sleep medicine specialist, and director at Nithra Institute of Sleep Sciences, Chennai, is also treating his patients remotely.

At a time when physical distancing is among the major measures used to fight COVID-19 pandemic, face-to-face consultation poses a very serious risk to both patients and doctors. Under these circumstances, remote consultations over the phone or video calls is a new way to help patients get access to healthcare services. On 25 March, the Government of India issued a set of guidelines for telemedicine or remote delivery of medical services [1]. The guideline legitimises the practice of remote consultations.

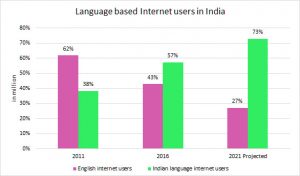

This is the situation of the urban scenario where telehealth consultations are available and have enough internet bandwidth to extend their capacity for such consultations. But what about rural India that needs healthcare services the most? Are the health centres in rural India with limited healthcare resources providing telehealth facilities during COVID-19?

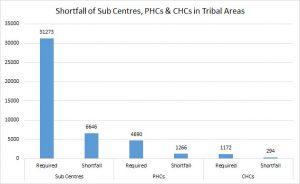

First, it is important to understand the structure of the rural public health system. It is a tiered structure. At the bottom of the pyramid are health sub-centres, catering to a population of 3,000 to 5,000 each, covering roughly five villages. These health sub-centres are usually manned by an Auxiliary Nurse Midwife (ANM) whose focus is on primitive and preventive healthcare services and to act as a referral to the primary health centres (PHCs) for curative services. PHCs are the first base for doctors, acting as referral units for six health sub-centres. PHCs act as a core and connected to community health centres (CHCs), followed by sub-district and district hospitals. There are over 1.5 health sub-centres, 25, 000 community health centres and 5000 public health centres in India. At the apex, there are medical colleges and advanced research institutes such as the All India Institute of Medical Sciences.

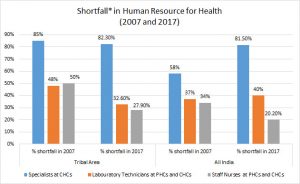

This tired structure looks impressive at first glance; however, the system is broken for large segments of the Indian population. According to Rural Health Statistics by the Ministry of Health & Welfare Services[2] only 11% sub-centres, 13% PHCs and 16% CHCs meet the Indian Public Health Standards. Moreover, a doctor-patient ratio is 1:2000 in India, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO). This means that six lakh villages where 70% of India’s population lives, the number of doctors is only a fourth of those in urban areas.

Thus, in times of COVID-19 crisis, adopting virtual healthcare approaches in rural health centres is essential. However, telemedicine is still a struggling concept in the countryside and even district-level healthcare centres are not able to do so.

Ostensibly, the National Teleconsultation Centre (CoNTeC)[3], an acronym for COVID-19 National Teleconsultation Centre launched by Union Minister of Health & Family Welfare Dr. Harsh Vardhan on 28 March 2020, is not meeting the requirements fully. CoNTeC has eight regional zones, establishing internet connection between medical colleges connected through the National Medical College Network (NMCN) with its National Resource Centre located at SGPGI, Lucknow. Presently, 50 medical colleges are registered under NMCN. It is reported that these medical colleges are connected through the National Knowledge Network (NKN) to provide telemedicine facilities.

However, these medical colleges are not connected with district hospitals and CHCs, which are located in the rural parts of the country. With 159 internet service providers in India, the broadband penetration in rural parts of the country is yet less than 16%, according to TRAI.

According to the Indian Public Health Standards (IPHS) for PHCs, CHCs, sub-district and district hospitals, the internet connectivity is provided for MIS (Management Information System)[4] and not telehealth services. The minimum internet speed allocated to district health centres is 2 Mbps to connect the doctor with the patient via video call. But this also is not available in most of the villages. As a result, the video quality turns out to be bad when district doctors try to connect with patients or health staff members. It thus becomes difficult to organise telehealth consultations. 2

Different sets of healthcare applications need different connection speeds. Table 1 below provides some applications that represent samples of activities typical of healthcare facilities of approximate download times to complete the transmission and download times at different network speeds. Individual healthcare facilities may use all, some, or none of these in addition to other network uses required for their operations (Hu, Wang, & Wu, 2006)[5].

Table 1. File size, transmission and download times at different connection speeds

| File type and size | Network transmission speed | ||||

| Type | Size | 4 Mbps | 10 Mbps | 20 Mbps | 50 Mbps |

| High Definition Video

Conferencing |

1.9 MBs | 23.8

seconds |

9.5

seconds |

4.8

seconds |

1.9

seconds |

| Tele-Pathology | 3 MBs | 2.3

seconds |

0.9

seconds |

0.5

seconds |

0.2

seconds |

| Tele-Diabetic Retinopathy

Screening |

5 MBs | 6.2

seconds |

2.5

seconds |

1.2

seconds |

0.5

seconds |

| Mammography | 160 MBs | 5 minutes | 2 minutes | 1 minute | 24.4 seconds |

| MRI study | 200 MBs | 6.3 minutes | 2.5 minutes | 1.2 minutes | 30.5 seconds |

According to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) recommendations, the following minimum bandwidth speeds are required to support electronic health record (EHR) system (Table 2) [6].

Table 2. Recommended bandwidth for healthcare providers

| Healthcare service | Bandwidth speed | Services |

| Single Physician Practice | 4 Mbps |

|

| Small Physician Practice

(2-4 physicians) |

10 Mbps |

|

| Rural Health Clinic | 10 Mbps |

|

Tables 1 and 2 clearly indicate that a 2 Mbps connection is not sufficient enough to provide all sorts of telemedicine services such as tele-radiology, tele-surgery, tele-ophthalmology, tele-pathology and tele-ICU services. The absence of infrastructure, internet connectivity, and lack of sufficient technical staff members and medical personnel have impeded the progress of telemedicine in rural parts of the country.

Stimulation wireless network model for telemedicine facility in rural health centres

One way to deal with the bandwidth issue is to create a wireless mesh network that can connect three to five medical colleges with a district health centre. The topology of the network requires that every terminal be connected to every other terminal in the network. The topology incorporates a unique network design in which each hospital on the network connects to every other, creating a point-to-point connection between every device on the network. The purpose of the design is to provide a high level of redundancy. If one network cable fails, the data always has an alternative path to get to its destination and the district health centre and replicating it further to CHCs and PHCs.

Another approach could be to estimate the unused bandwidth available in the region which can further be used for connecting district health centres. Depending upon the availability of the network, different models can be adopted.

Other suggestions that the government can consider are to allocate high-speed wireless frequency band of unused spectrum (V band or 60 GHz, which is like short-range wireless optic fibre) and TV White space for the telemedicine facility and to be used for community services.

To sum up, the coronavirus crisis has made the need for high-speed, reliable internet clear. The current isolation period is a gentle reminder to authorities concerned about the necessity of an adequate internet connectivity and higher bandwidth in rural India that can potentially connect us and enable us to have a better healthcare facility all the time.

References

[1] Telemedicine Practice Guidelines; https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/Telemedicine.pdf

[2] Rural Health Statistics; https://www.thehinducentre.com/resources/article31067514.ece/binary/Final%20RHS%202018-19_0-compressed.pdf

[3] National Telemedicine Portal; https://nmcn.in/about.php

[4] Indian Public Health Standards; https://nhm.gov.in/index1.php?lang=1&level=2&sublinkid=971&lid=154

[5] Hu et al. (2006). Mobile telemedicine sensor networks with low-energy data query and network lifetime considerations. Mobile Computing, IEEE Transactions on, 5(4), 404-417; 10.1109/TMC.2006.1599408

[6] HealthIT.Gov; https://www.healthit.gov/faq/what-recommended-bandwidth-different-types-health-care-providers

Date: 20 July 2020

Author: Ritu Srivastava

Focus Areas: Digital Health

What We Do: Research & Advocacy

Resource Type: Research Analysis